The Delight and the Danger of Bothness: Embracing Contradictions in Nonprofit DEI Work

At a recent training of circle facilitators at which I interned, one pointed out the practical qualities of circle process, that it includes such pragmatic benefits. The centerpiece, for example, provides a visual anchor and minimizes the potential awkwardness of gazing at one another for too long. The talking piece mitigates against dominant personalities and affords those less likely to speak the opportunity to be heard. When my turn arrived, I vocalized agreement, but uplifted the opposite notion: that circle is a microcosm of the world we envision, one of a “million experiments” we abolitionists practice for better ways of being human in community. That “visual anchor” is ceremonial, rooted in Indigenous traditions worldwide, representing the elements of nature (water, fire, etc.) pregnant with divine symbolism. In this sense, I find circle quite mystical. My take stood antithetical to the previous remark about practicality, but I held them together and out of my mouth spilled: “I’m really delighting in the bothness.”

I offer this term I accidentally coined as an admittedly cutesy framing of one of my dearest values. Usually referred to as both/and thinking, bothness points to the reality that contradictions are often true at once and that seldom is anything so simple as a spectrum connecting two poles in the first place. Bothness also denotes the posture and choice of embracing this reality, a way of being that actively disrupts dichotomous worldviews. It’s the quest to dismantle binaries wherever they encumber us.

To be sure, it’s easy for me to cherish this because it’s my default setting: I naturally zoom out to spectate at the matrix of possibilities and much prefer any available gray area. And I recognize this tendency as a privilege insomuch as either/or thinking, in turn, constitutes a trauma response for many: a now-close friend who witnessed the “bothness” anecdote told me later that her instinct differs, that faced with conflict, only two extremes ever appear, which she attributes to her trauma history. Moreover, part of bothness’ appeal is its connection to an ancient spiritual truth: nonduality, the unity of creator and creation, sacred and profane, divine and human. It’s what Bede Griffiths appropriated as advaita, literally meaning “not two.”

Indeed, a nerd about spirituality, I value bothness because of its theological profundity. But instead of regurgitating others’ wisdom about nonduality, while tempting, here I explore how this perspective serves as a tool that has aided me in navigating contradictions in the nonprofit industrial complex, specifically the homelessness sector and so-called Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) efforts in the workplace. Lest it seem a panacea, though, I caution that bothness also threatens progress.

BOTHNESS AT WORK

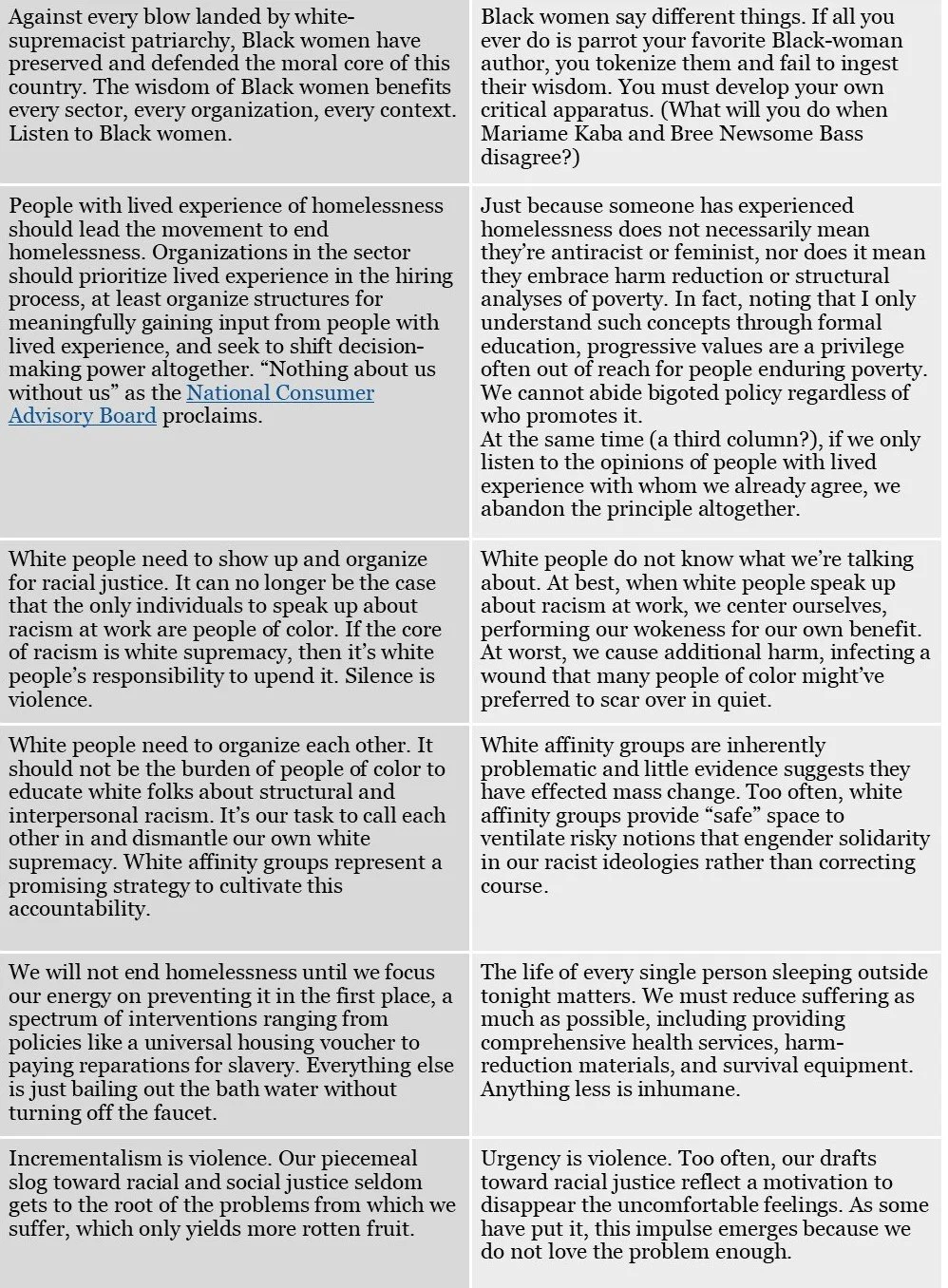

Consider a sample of dichotomies that show up in my work all the time:

In my experience working with and for nonprofits in the movement to end homelessness, specifically those pursuing visions of racial equity, such contradictions provoke either misguided action or paralysis. Either/or thinking (eitherness? Nah) regards binaries like two horses attempting to rescue an entrenched carriage but pulling in opposite directions: better to sever one tether in favor of the other trajectory or to risk the vessel’s destruction. For this reason, at one extreme, we witness some nonprofits celebrate themselves for recruiting Black staff or Board members but who onboard them into hostile environments unwilling to evolve. And occasionally, these same Black colleagues perpetuate harmful ideologies and reinforce white-supremacist structures; these nonprofits have mounted the “representation matters” horse to the exclusion of racial justice. At the other pole, some nonprofit Boards and senior staff consist mostly of woke white people, the ones who may say the right things but whose very occupation of their positions (like my own) serves to displace Black and Brown candidates; this the “limits of representation” horse.

Bothness, on the other hand, perceives these opposites not as tug-of-war but like stilts, where rescue requires both, and indeed forward motion facilitates such balance much better than stagnation. Bothness declares, in the above example, that representation is necessary and insufficient. Nonprofits will scarcely embody anything akin to racial justice when comprising mostly white people and lived experience of racism does not equate to antiracist analysis. Both.

But the carriage is just as likely to remain mired in the quicksand. In so many cases, nonprofits take action in support of whatever advice they first internalized only to return to the status quo when criticized with the opposite truth. For example, the phenomenon of a “DEI Director” (or equivalent position) is fraught. Predating 2020 but certainly catapulted since then, DEI has corporatized into an industry unto itself. At a previous workplace, my colleagues and I found that our DEI committee (which we only received approval to form amidst the 2020 uprisings), composed of staff volunteering their time from across departments lacked sufficient resources, expertise, and racial representation to carry out our goals. It was necessary, we believed, to hire an expert whose full-time job was devoted to this work, and indeed our DEI journey accelerated when we did.

The risk of hiring a DEI Director, many have found, is that it can serve to outsource everyone’s responsibility to uproot racist norms onto one person, and the hire often only occurs in response to a crisis. “Racial tension? Call the DEI Director to fix it.” Too often, DEI Directors enjoy little meaningful power, erected instead as symbols of the organization’s inclusive achievement. And because these positions are almost always (and should be) occupied by people of color, this responsibility exacts a toll of retraumatization, tokenization, and psychological violence. Not to mention that DEI can rarely accomplish more than harm reduction because it presumes the legitimacy of the racist and oppressive institutions it seeks to reform.

“To choose nonaction in a racist society is to choose racism.”

One horse hoists toward putting your money where your mouth is: hire a DEI director and empower them to change the organizational culture. The other resists, claiming it’s everyone’s responsibility to disrupt toxic norms. More often than not, the response to this tension is to do nothing, and to choose nonaction in a racist society is to choose racism. What if, instead, we chose bothness? What if we empowered whole departments to lead the entire organization in antiracist and anti-oppressive culture while lamenting their necessity in the first place? What if everyone’s job was DEI director, in a sense, but we followed the leadership of a trusted expert and continuously interrogated our intentions and process? What if we trudged onward letting the grime coexist with grace?

Danger! Beware!

In every instance in which I embrace bothness, the situation benefits from it, and I, in turn, get unstuck. I also receive sincere pleasure and relief; what a gift to be liberated from the perceived constraints of contradiction! When you can step into the gray rather than retreat to clearly defined corners, fear often makes way for joy. In fact, bothness produced this website. One truth held me back for ages, that we have enough white men on the internet, and certainly need none who espouse any acumen in racial-justice organizing. But another truth coexists: as toxic masculinity plunders the world, we need men to access and model vulnerability, introspection, and creativity. I attempt to hold both together as I stumble through this project, expecting that I’ll be corrected eventually and then change my mind.

But there is bothness to bothness. For one thing, I employ either/or thinking in positioning both/and in opposition to either/or, so I contradict myself from the start. Moreover, on a practical note, my tendency toward both/and thinking often burdens me with indecision and angst, perceiving the merits of multiple tacts at the expense of any motion. Less lightheartedly, bothness risks misappropriation and even weaponization.

Bothness should not be interpreted as moderate politics. In arguing that we ought embrace contradictions, I do not mean that there is no correct position, nor that any political ideology weighs the same as its opposite. Indeed, if political orientations really do exist on a spectrum, my own situate about as far left as it goes; bothness doesn’t position progressive and conservative as yin and yang, necessary for one another’s existence. Rather, bothness helps us move forward with contradictory truths, not just any polarity. Some notions exist for violence and oppression, and there is no bothness in harm.

“Bothness helps us move forward with contradictory TRUTHS, not just any polarity.”

Furthermore, we ought not deploy bothness as a trump card to deflect criticism. How many white-led nonprofits fly the “representation alone is superficial” flag in order to continue hiring white people disproportionately? That opposites coexist does not mean I, especially as a white man, can never be wrong; indeed, bothness acknowledges that I often am and helps me evolve rather than freeze.

Contradictions as Invitation

Bothness offers us the opportunity to welcome contradictions as invitations for deeper inquiry into complexity, which is often uncomfortable, but inches us closer to liberation. It beckons us to ask questions, which lead to more questions, like:

How do these opposite truths show up in our particular context?

Who is espousing these options? When?

Who benefits from each?

How does our moment in history and the national dialog, such as that exists, offer clarity?

What do we need to learn in order to make a more educated decision?

May our hearts be open to the benefits of bothness, then, along with the gift of the corrections that follow.